Introduction

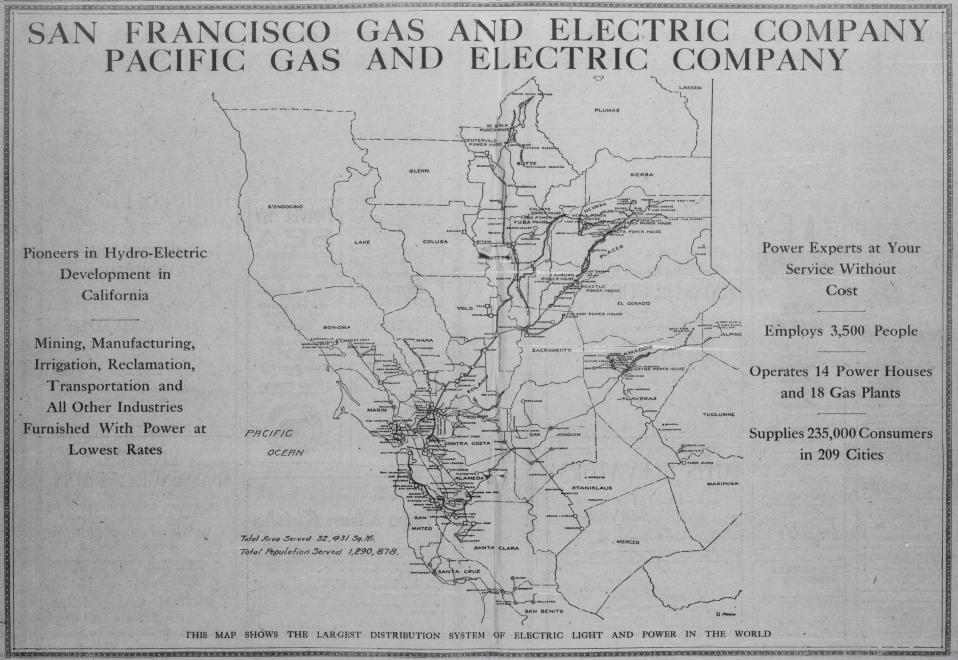

To get a grasp of why Pacific Gas & Electric Company (PG&E) became such a major power in California, it requires a historic review of the events leading up to the company’s formation. It helps to understand who was behind its formation and claim by 1911 of being the world’s largest distributor of electricity. Even though it had lost its claim as the largest distributor to J.P. Morgan’s Electric Bond and Share Co. within a decade it claimed to be the biggest in the US once again by the 1960’s.

To get a grasp of why Pacific Gas & Electric Company (PG&E) became such a major power in California, it requires a historic review of the events leading up to the company’s formation. It helps to understand who was behind its formation and claim by 1911 of being the world’s largest distributor of electricity. Even though it had lost its claim as the largest distributor to J.P. Morgan’s Electric Bond and Share Co. within a decade it claimed to be the biggest in the US once again by the 1960’s.

Please click on the SF History tab for the history about the intimate relationship between the heirs of the Southern Pacific empire and PG&E.

SF History

Brief History of Northern California’s Energy Development

California’s history is usually wrapped up in romantic terms from the Bear Flag Rebellion, the Gold Rush or to the coming of the first Transcontinental Railroad. The real stories, however, offer quite a different picture. California’s history of energy development in particular reveals a much darker side. The state’s first major source of energy came from whale oil. According to the “California Register” over 15,000 men on 650 ships sailing from the west coast produced 1,306,567 gallons of whale oil in 1855. The killing of whales for lighting and other uses slowed by 1860 with the development of kerosene and mineral oils, but continued in California well into the 20th Century for the use in other whale byproducts. There has never been any coal in California so it had to be imported.

The first use of urban lighting goes back to the age of Greece. The Persian scholar Rhazes first demonstrated the use of coal gas in the 9th century, later known by its American corporate patent as Kerosene. London was employing candle based street lighting by the 15th century with Paris requiring it by 1529. However, the first modern use of coal gas was demonstrated by William Murdoch when he lit up his own British home in 1792 – with street lighting first demonstrated in Paris by 1829. Contrary to the American myth pushed by J.P. Morgan and his General Electric empire the first electric light was invented in London by Humphrey Davy in1806. Gas lights would first show up on London streets in 1848.

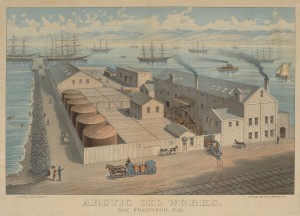

California’s first street gas lighting would be produced by the San Francisco Gas Company starting in 1852. Its founder, Peter Donahue, came up with the idea as a byproduct from his other company, the Union Iron Works a firm that also play a prominent role in the city’s industrial future. St Joseph Missouri, followed by Cleveland, then San Francisco’s Palace Hotel were the first US cities to use Charles Brush’s method of Arc lighting in 1879. All predated Thomas Edison’s Direct Current (DC) driven lighting demonstration on December 31st, 1879 or commercial service in New York City that started in 1882. American experiments with hydroelectric powered arc lights followed in 1880, with the first California hydro facility starting up in San Bernadino in 1886.

Edison’s plan to use DC current to light up America would die within years as it was incapable of being transmitted over long distances. He would be shamed nationally by his vicious public campaign to stop Nicola Tesla’s Alternating Current (AC) from taking over that started with the electrocution of animals large (elephants) and small that culminated in the horrific frying of a convicted killer in the country’s first electric chair.

Edison’s primary financial backer, J.P. Morgan took Edison’s electric company from him in 1892 and renamed it the General Electric Company.  Morgan would also fire the company’s head man Samuel Insull that initiated a life long battle that later became one of the country’s biggest scandals during the height of the great depression. Morgan used subversive financial tactics to force his main competitor George Westinghouse to give him Nicola Tesla’s patents for AC power. It was not until after 1888, when Nicola Tesla invented AC current that enabled the ability to transmit electricity over long distances, that the idea of using Sierra Mountain water to produce electricity took hold in California.

Morgan would also fire the company’s head man Samuel Insull that initiated a life long battle that later became one of the country’s biggest scandals during the height of the great depression. Morgan used subversive financial tactics to force his main competitor George Westinghouse to give him Nicola Tesla’s patents for AC power. It was not until after 1888, when Nicola Tesla invented AC current that enabled the ability to transmit electricity over long distances, that the idea of using Sierra Mountain water to produce electricity took hold in California.

Windmills have been around for at least 3,000 years and can be found historically in many parts of the world. In the mid 19th Century Daniel Halladay would use wood to enhance the old fan mill design that used canvass for blades. He also hung the top of the mill on a rotating ring using flyweights to make the wind mill fully self regulating. Leonhard Wheeler would make additional upgrades that became known as the American wind turbine. Primary uses were for milling grain, pumping water, and sawing wood. Charles Brush would be the first to produce electricity from a windmill in 1888. They could be  found around the Bay Area by the 1860’s at rail stations, even in San Francisco’s Pacific Heights or at the extensive salt works dotting the South Bay.

found around the Bay Area by the 1860’s at rail stations, even in San Francisco’s Pacific Heights or at the extensive salt works dotting the South Bay.

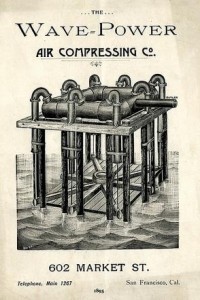

Of interest is that early forms of tidal power generation was already being promoted at the end of the 19th Century. As early as 1880 the use of tidal energy to pump water up into water towers were was demonstrated in Connecticut. Tide mills as they were known at the time, were used primarily to mill grain. But according to a local 1895 advertisement it is was used to produce compressed air.

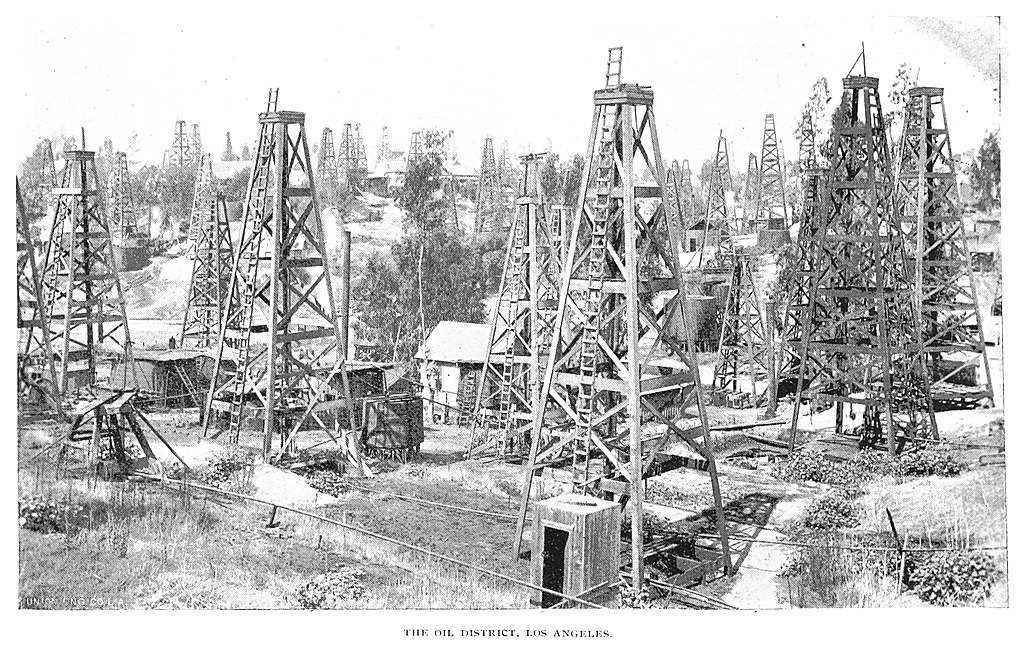

The last major source of power to hit California was the discovery of oil and its use to produce electricity. The first  successful oil well drilled in the state was in Humboldt County in 1865. In 1879, Charles Felton, George Loomis and Loyd Tevis formed the Pacific Coast Oil Company. Major oil production started in 1893, reaching 45 million barrels of oil by 1908, making California the largest oil producer in the country. There were two major sources – crude oil used directly to generate electricity, and water-gas, that would then become oil-gas, or what we call “natural gas” today with the first facility coming online by 1899. The Pacific Coast Company would be sold to John Rockefeller in 1900 and renamed Standard Oil of California or Chevron today. Hollywood would popularize the massive oil development in Los Angeles, but by 1901, the San Joaquin Basin was the main oil-producing region of California. California’s massive oil supplies would slowly whither away due to heavy exploitation. Following the Arab oil embargo of 1973, the use of oil for electric production was quickly phased out of use in the US.

successful oil well drilled in the state was in Humboldt County in 1865. In 1879, Charles Felton, George Loomis and Loyd Tevis formed the Pacific Coast Oil Company. Major oil production started in 1893, reaching 45 million barrels of oil by 1908, making California the largest oil producer in the country. There were two major sources – crude oil used directly to generate electricity, and water-gas, that would then become oil-gas, or what we call “natural gas” today with the first facility coming online by 1899. The Pacific Coast Company would be sold to John Rockefeller in 1900 and renamed Standard Oil of California or Chevron today. Hollywood would popularize the massive oil development in Los Angeles, but by 1901, the San Joaquin Basin was the main oil-producing region of California. California’s massive oil supplies would slowly whither away due to heavy exploitation. Following the Arab oil embargo of 1973, the use of oil for electric production was quickly phased out of use in the US.

Unlike the Northeast’s use of water power for textiles, California’s initial development of water power would be used for strip mining purposes. The first major fallout from the use of high pressure water for mining was the contamination of San Francisco Bay by mercury, as well as the serious erosion across the Sierra foothills. Germany would be the first to demonstrate hydroelectric transmission over distances in 1891, with the Folsom Powerhouse built by Gallatin and Livermore (close associates of the Southern Pacific crowd) using forced prison labor. It was the first facility to transmit three phase AC electricity over a long distance in the U.S. – 22 miles to Sacramento to power street lights and the capital’s trolley system in 1893.

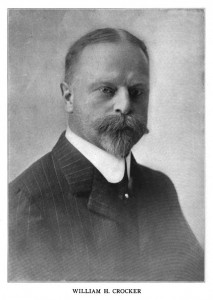

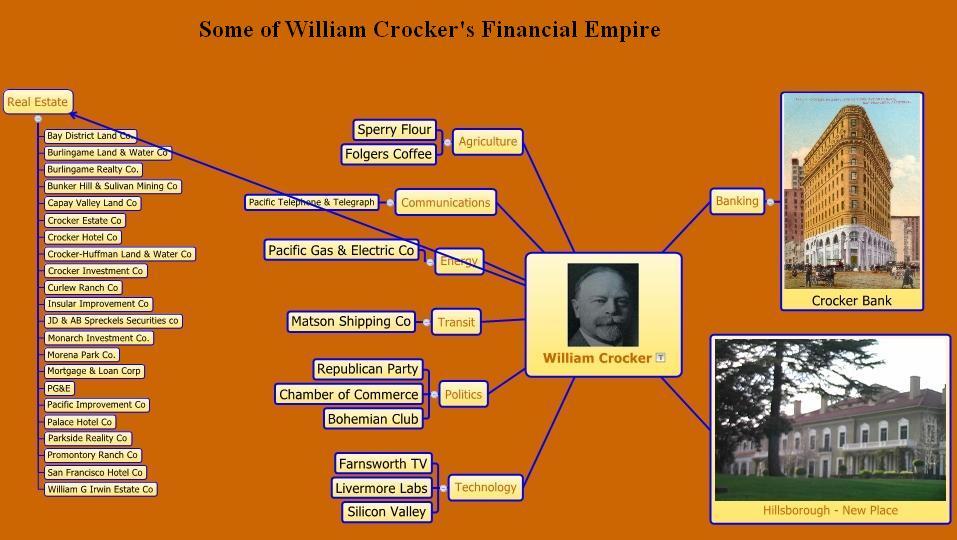

William Crocker, the youngest son of Charles Crocker (co-founder of the Southern Pacific railroad empire) would be drawn into the development of hydroelectric power in 1895 for mining operations by Prince Poniatowski (royal heir of Poland) who married his wife’s sister. The Prince supposedly came up with the idea of building a hydroelectric system that would supply power to San Francisco. Crocker and the Prince would cut deals with J.P. Morgan’s General Electric company to form the Standard Electric Company of California to build the Electra Powerhouse in Amador County that would eventually send power all the way to the city. The immense financial resources Crocker had at his disposal played the pivotal role in the formation of Pacific Gas & Electric Company (PG&E).

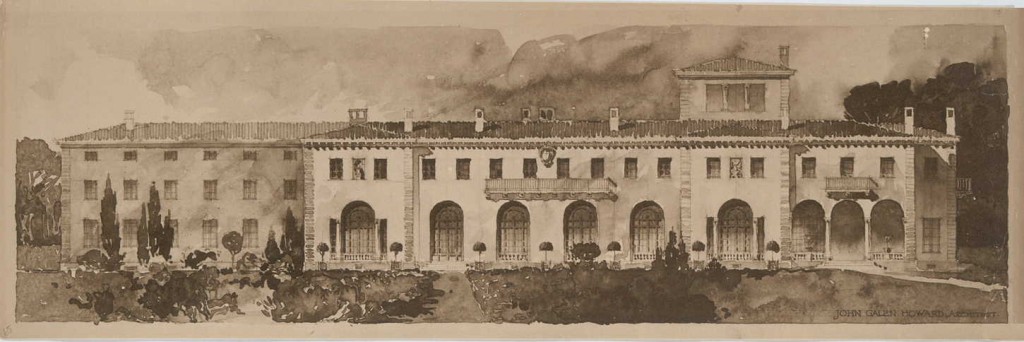

William Crocker would become one of the most powerful capitalists in American history. His father Charles bought control of the Woolworth bank and gave it to him as a graduation present that became Crocker Bank. It eventually became one of the biggest in the country. This was no ordinary bank — only owners of companies were its clients during its early history. Crocker was quietly known as the Rockefeller of the West. His sister had even married into the Aldrich-Rockefeller clan. His older brother Charles II was vice-president of the Southern Pacific at the time of the Pullman Strike in 1896. He liked to be referred as Colonel Crocker, dressing in full military uniform, having been made a colonel in the state’s militia that killed dozens of workers in stopping the strike in California. Willie Crocker would head the California republican party as well as the state Chamber of Commerce. His wife was from the Sperry family, one of the state’s most powerful agribusinesses. William sat on dozens of corporate boards and real estate companies, even being labeled the Banker of Princes due to his relationship with Poniatowski. The most powerful of these Crocker presided over besides his PG&E and Pacific Bell interests was the Pacific Improvement Company – the Central and Southern Pacific’s contractor front that built its rail lines and the majestic Del Monte Hotel resort in Monterey. It owned nearly 10 million acres of California lands. It eventually changed its name to Catellus Development Company that held some of the city’s most valuable real estate. Crocker led the Southern Pacific’s 2nd generation that regrouped after the state’s populist movement attempted to breakup the Octopus.

William Crocker would become one of the most powerful capitalists in American history. His father Charles bought control of the Woolworth bank and gave it to him as a graduation present that became Crocker Bank. It eventually became one of the biggest in the country. This was no ordinary bank — only owners of companies were its clients during its early history. Crocker was quietly known as the Rockefeller of the West. His sister had even married into the Aldrich-Rockefeller clan. His older brother Charles II was vice-president of the Southern Pacific at the time of the Pullman Strike in 1896. He liked to be referred as Colonel Crocker, dressing in full military uniform, having been made a colonel in the state’s militia that killed dozens of workers in stopping the strike in California. Willie Crocker would head the California republican party as well as the state Chamber of Commerce. His wife was from the Sperry family, one of the state’s most powerful agribusinesses. William sat on dozens of corporate boards and real estate companies, even being labeled the Banker of Princes due to his relationship with Poniatowski. The most powerful of these Crocker presided over besides his PG&E and Pacific Bell interests was the Pacific Improvement Company – the Central and Southern Pacific’s contractor front that built its rail lines and the majestic Del Monte Hotel resort in Monterey. It owned nearly 10 million acres of California lands. It eventually changed its name to Catellus Development Company that held some of the city’s most valuable real estate. Crocker led the Southern Pacific’s 2nd generation that regrouped after the state’s populist movement attempted to breakup the Octopus.

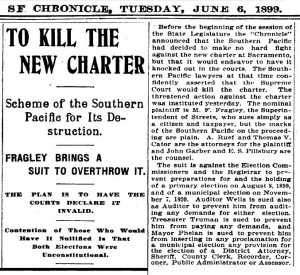

But in 1898 the city of San Francisco passed a new city Charter that stunned the Southern Pacific Crowd, calling for the municipal ownership of all utilities from phone service, water, transit and last but not least, electricity. All other utilities except for electricity was under Southern Pacific’s control. Although the Octopus would file suit against the Charter, it failed to block its implementation.

But in 1898 the city of San Francisco passed a new city Charter that stunned the Southern Pacific Crowd, calling for the municipal ownership of all utilities from phone service, water, transit and last but not least, electricity. All other utilities except for electricity was under Southern Pacific’s control. Although the Octopus would file suit against the Charter, it failed to block its implementation.

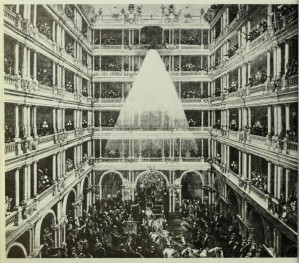

By the turn of the century, there were fourteen electric power companies headquartered in San Francisco. In many cases, these companies were using imported coal, incurring public anger as they filled the sky with soot. Prices and service varied, with poorer communities receiving none at all.

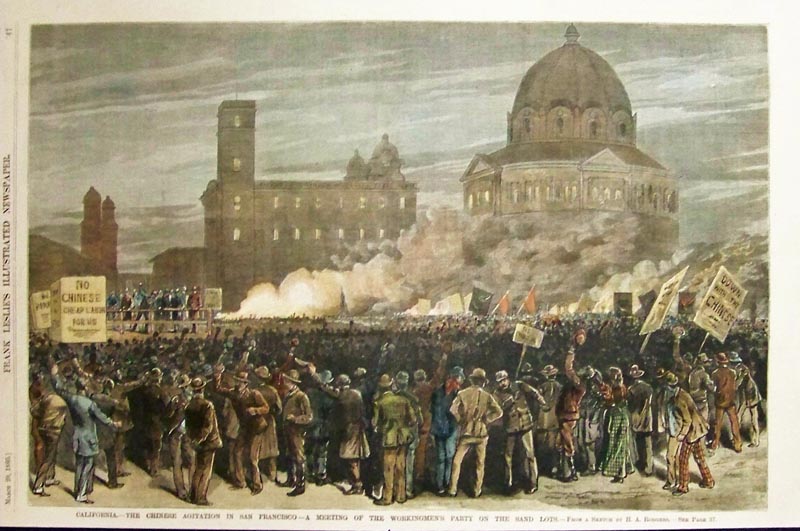

`There was no clearer example of the growing demand to break up monopolization than with the Southern Pacific Empire. By 1880, the Southern Pacific’s Big Four (Crocker, Huntington, Hopkins & Stanford) were individually worth over $80 million, making them one of the wealthiest business groups in the country. Their control of nearly 10% of the state’s land and events like the infamous Mussel Slough Affair helped propel their image as a vicious, power hungry bunch of Robber Barons.

Public anger towards them was so great that in 1878, following protests in San Francisco, that included the famous march by Dennis Kearney up to Charles Crocker’s mansion on Nob Hill culminating in the call to burn it down, the California Workingman’s Party was formed. The Party would gain control of the state legislature and rewrite the state’s constitution to include the formation of the Railroad Commission meant to regulate the abuses of Southern Pacific and other rail companies in the state.

One of their biggest allies in the city was William Bourn. His father had gained control of the Fireman’s Fund Insurance Company, before taking control of the Empire Gold Mine – the wealthiest mine in the state. He would then get control of the Spring Valley Water Company in alliance with other SP allies. Finally he would become the largest investor in the San Francisco Gas & Electric Company, the biggest electric company in San Francisco. While waiting for his Filoli Mansion to be completed, he stayed at his friend William Crocker’s spare mansion in Hillsborough built originally for Prince Poniatowski, who decided to go back to France in 1903. Bourn would buy into the idea of creating one large single electric monopoly. The rest of the work would be a matter of a gentlemen’s agreement.

Crocker bought up all the electric companies between San Jose and San Francisco, then turned to Frank Drum for the next phase of the plan to create an electric monopoly. Drum sat on the Crocker bank’s board of directors and was working for Loyd Tevis, the former head of Wells Fargo, Southern Pacific, Spring Valley Water Company, co-founder of Chevon and one of the state’s largest landowners. Later known as the Kern County Land Company, it was acquired by Tenneco that became one of the largest agribusiness companies in the country. Tevis had cooked up the successful plan to steal Wells Fargo from its real owners in 1865. Frank’s mentor was Henry Scott, who just happened to be William Crocker’s mentor and next door neighbor in Hillsborough. Scott was the head of the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Company and the Union Iron Works that had built many locomotives for Southern Pacific. He was a prominent war monger that got him many government contracts to construct battleships at the Union Iron Works.It would be Frank Drum’s job to pull the financing and people together for the formation of the California Gas & Electric Company in 1901.

Crocker bought up all the electric companies between San Jose and San Francisco, then turned to Frank Drum for the next phase of the plan to create an electric monopoly. Drum sat on the Crocker bank’s board of directors and was working for Loyd Tevis, the former head of Wells Fargo, Southern Pacific, Spring Valley Water Company, co-founder of Chevon and one of the state’s largest landowners. Later known as the Kern County Land Company, it was acquired by Tenneco that became one of the largest agribusiness companies in the country. Tevis had cooked up the successful plan to steal Wells Fargo from its real owners in 1865. Frank’s mentor was Henry Scott, who just happened to be William Crocker’s mentor and next door neighbor in Hillsborough. Scott was the head of the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Company and the Union Iron Works that had built many locomotives for Southern Pacific. He was a prominent war monger that got him many government contracts to construct battleships at the Union Iron Works.It would be Frank Drum’s job to pull the financing and people together for the formation of the California Gas & Electric Company in 1901.

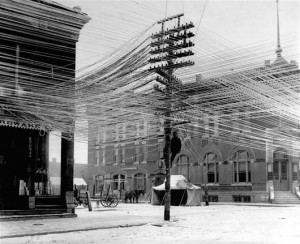

From the early 1890’s, businessmen across the country were founding electric companies. Most communities were served by number of them, all competing for the same customers. Quality and service varied widely, becoming a public concern. For example, electric poles could have dozens of competing wires making repairs dangerous for workers. It wasn’t long before a national movement calling for municipal control over electricity production emerged. By 1900, there were over 700 municipally owned powerhouses in the country vs. 2,000 private ones. Los Angeles and San Francisco both started campaigns to take control of their power and water needs with SF’s Mayor Phelan doing a study that selected Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite as the ideal candidate for the city.

From the early 1890’s, businessmen across the country were founding electric companies. Most communities were served by number of them, all competing for the same customers. Quality and service varied widely, becoming a public concern. For example, electric poles could have dozens of competing wires making repairs dangerous for workers. It wasn’t long before a national movement calling for municipal control over electricity production emerged. By 1900, there were over 700 municipally owned powerhouses in the country vs. 2,000 private ones. Los Angeles and San Francisco both started campaigns to take control of their power and water needs with SF’s Mayor Phelan doing a study that selected Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite as the ideal candidate for the city.

John Martin (coal dealer) and Eugene De Salba Jr. (his French father owned a plantation in Panama) became early promoters of building hydroelectric powerhouses in the Sierra’s. De Salba turned to the former head of the SP’s Pacific Improvement Company and Romulus Colgate to build their first hydroelectric powerhouse (Rome) along the Yuba River. After constructing a second Colgate project, they organized the Central California Gas & Electric Company in 1901.

John Martin (coal dealer) and Eugene De Salba Jr. (his French father owned a plantation in Panama) became early promoters of building hydroelectric powerhouses in the Sierra’s. De Salba turned to the former head of the SP’s Pacific Improvement Company and Romulus Colgate to build their first hydroelectric powerhouse (Rome) along the Yuba River. After constructing a second Colgate project, they organized the Central California Gas & Electric Company in 1901.

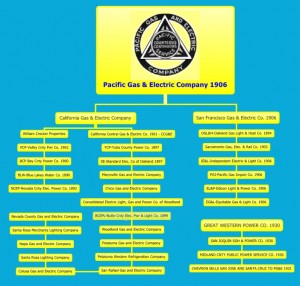

This company was a merger of 14 small electric distribution companies from Chico to San Rafael. Shortly after Martin and De Salba’s holding company was formed, Frank Drum would convince them to merge with his interests, resulting in the California Gas & Electric Company (CG&E) a few months later. These two early characters and Colgate were pushed out of PG&E by 1913 as Wall Street funding took over. Soon after PG&E’s formation, De Salba who some called the Father of PG&E would purchase the prominent Hillsborough community center’s Villa and 12 acre property called El Cerrito not far from William Crocker’s mansion. El Cerrito originally belonged to WDM Howard, one of San Francisco’s most prominent founding members (Howard Street is named after him). The original El Cerrito estate included all of what is today’s Hillsborough that would be populated by some of the wealthiest people in the country after the 1907 earthquake. After dropping out of PG&E De Salba moved into oil speculation.

However, CG&E was smaller than the San Francisco Gas & Electric Company (SFG&E) with roots going back to 1852. William Crocker and William Bourn’s plan to merge the two operations was almost ready. However, one of SFG&E’s largest investors was Rudolph Spreckels whose family had been actively fighting the Southern Pacific Octopus, using its own major daily newspaper, the San Francisco Call as their voice.

Had it become public knowledge that Crocker’s plan to counter the 1898 Charter by building a large private holding company covering most of Northern California, Spreckels would have launched a full scale counter attack. In fact, Spreckels would later play a prominent role in promoting proposition 19 (the statewide Water and Power act) in 1922. But with Drum taking the lead, Crocker’s financial role in PG&E’s formation disappeared. The planned merger that included a complete buyout of all of SFG&E’s major investors, plus Oakland’s biggest electric company would take even larger financial resources. N.W. Halsey, an agent of J.D. Rockefeller’s National City Bank was brought in to pull together the final deal that was announced in October of 1905, but not finalized until early 1906. National City Bank, known today as CitiCorp, would continue to be PG&E’s Wall Street front up until the death of William Crocker in 1937. In 1939, the House of Representative’s Temporary National Economic Committee on the concentration of wealth in the United States determined that Crocker was in control of PG&E.

Had it become public knowledge that Crocker’s plan to counter the 1898 Charter by building a large private holding company covering most of Northern California, Spreckels would have launched a full scale counter attack. In fact, Spreckels would later play a prominent role in promoting proposition 19 (the statewide Water and Power act) in 1922. But with Drum taking the lead, Crocker’s financial role in PG&E’s formation disappeared. The planned merger that included a complete buyout of all of SFG&E’s major investors, plus Oakland’s biggest electric company would take even larger financial resources. N.W. Halsey, an agent of J.D. Rockefeller’s National City Bank was brought in to pull together the final deal that was announced in October of 1905, but not finalized until early 1906. National City Bank, known today as CitiCorp, would continue to be PG&E’s Wall Street front up until the death of William Crocker in 1937. In 1939, the House of Representative’s Temporary National Economic Committee on the concentration of wealth in the United States determined that Crocker was in control of PG&E.

Just months after PG&E’s 1906 formation, the company’s broken gas mains played a major role in much of the city burning down. Shortly after the earthquake Rudolph Spreckels hired the Burns detective agency that uncovered the details of what has been called the Abe Ruef Scandal, an affair that should more appropriately be known as the Southern Pacific Graft Wars. The San Francisco Board of Supervisors resigned after taking a plea bargain that exposed how Abe Ruef had been using bribes by Pacific Telephone & Telegraph, Spring Valley Water Company, Leland Stanford’s former SF trolley system (United Railroads) and PG&E to get special contracts with the city. Ruef claimed that Frank Drum had secretly retained him to work for PG&E at $1,000 a month. When PG&E attempted to get an 10 cent increase in gas rates, Ruef was given an additional $20,000 by Drum to bribe the Board of Supervisor for the higher rates. The politicians lost their jobs, Ruef went to jail but attempts to prosecute the businesses that had resorted to bribery stalled either to corrupt judges or thrown juries.

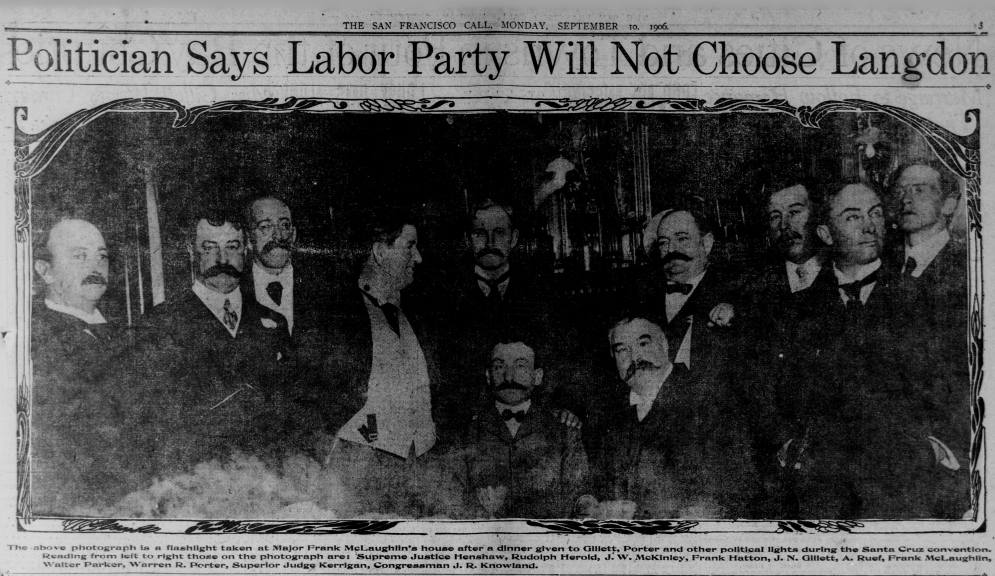

In what was dubbed the “Shame of California”, the above photograph showed Ruef (center seated) with many of the state’s most powerful political players as they cut a deal to determine who the next governor would be. For example State Supreme Court Justice Henshaw (on far left) would play a prominent role in keeping the Ruef scandal out of the courts, while directly behind Ruef would be the next governor, James Gillett. On the right is the Senator J.R. Knowland who would become the owner of the powerful Oakland Tribune.

By 1910 the republican controlled state legislature passed a new law allowing PG&E to use Eminent Domain to take public and private properties for it to build hydroelectric facilities anywhere in the state. In one instance the company took the beloved ranch of the founder of UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library. By 1919, the controversy of private companies being able to take property this way had gone nationwide. As a compromise the Federal Power Act was passed that granted private speculators a 50 year lease on public lands that could then be returned to public control after expiration. Hundreds of dams nationwide were thus built and controlled by Wall Street speculators.

But PG&E would have one last major political problem – The labor movement in San Francisco. Since the founding of the Workingman’s Party in the late1870’s, an ever increasingly more powerful labor movement was demanding good pay, and working conditions in the City. Much of the rank and file were strong opponents of the Southern Pacific Crowd that held political and economic control of the state since the creation of the first transcontinental railroad in 1869. This mood grew dramatically after the death of 25 Sacramento union workers at the peak of the 1896 Pullman strike.

But PG&E would have one last major political problem – The labor movement in San Francisco. Since the founding of the Workingman’s Party in the late1870’s, an ever increasingly more powerful labor movement was demanding good pay, and working conditions in the City. Much of the rank and file were strong opponents of the Southern Pacific Crowd that held political and economic control of the state since the creation of the first transcontinental railroad in 1869. This mood grew dramatically after the death of 25 Sacramento union workers at the peak of the 1896 Pullman strike.

Labor would play a vital role in the passage of the 1898 charter that called for the municipalization of public utilities like electricity, telephones, water and public transit. PG&E would face a system wide strike in 1913 by a radical wing of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) that included the dynamiting of power lines across the entire PG&E-system. Even though the city’s Labor Council supported the radical strategy it was forced to back away from supporting the strike under a threat by the American Federation of Labor. The radical local was forced to disband, thereby ending PG&E’s labor problems. However, the company would play a prominent role in attacking the city labor movement’s demand for closed shop unions. The labor movement’s support for public utility ownership would set them on a course to full scale battle with the 1922 Water and power Act, Hetch Hetchy and then the Central Valley Project. The battle over public control led by labor activists would extend up through 1947 – or until the passage of the Taft Hartley Act eviscerated the country’s labor movement. Labor would keep close track of PG&E’s campaigns to attack public power.

1922 Power War

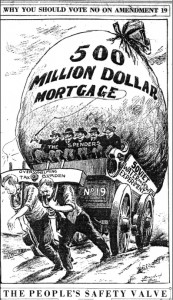

After years of attempts to introduce state legislation that would setup a state owned water and power system, activists from across the state took their plan directly to the people of California, making it on the ballot as Proposition 19 in 1922. PG&E and Southern California Edison would finance a front group called the Greater California League that would spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to block the ballot initiative that would resurface several more times in the 1920’s until President Franklin Roosevelt used his authority to federalize the project that would eventually be known as the Central Valley Project.

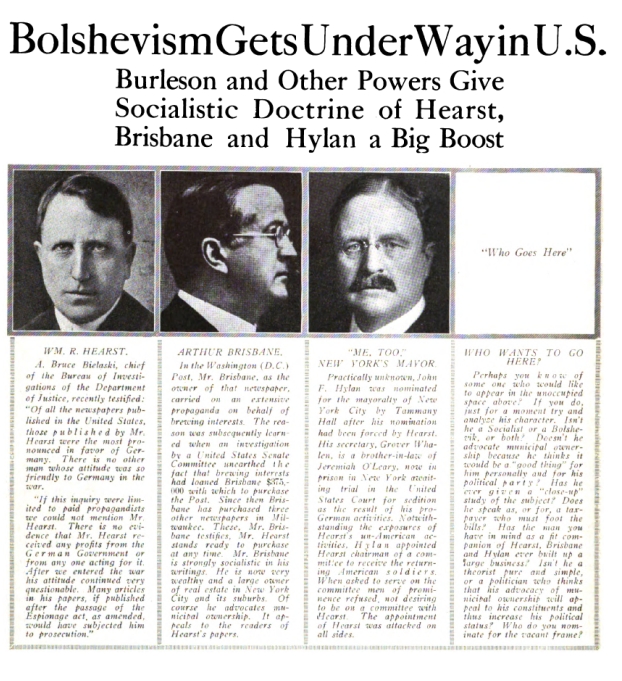

During the 1922 campaign, PG&E would use its extensive network of small town newspapers and bankers to launch a smear campaign against the proposal claiming that it was an attempt to Sovietize California. The smear tactics were such that even William Randal Hearst who supported the idea of public ownership of power was called a communist in the organized journals setup to promote private control over electricity across the country.

PG&E and Southern California Edison would mount a massive statewide campaign spending nearly half a million dollars that killed the initiative claiming the project was a socialist plot to take over California! And has documented, the public vs. private battle over control of public utilities would forever be framed in such terms even though most of Europe had moved towards public power as it was shown that it was cheaper and willing to distribute power to everyone not just the wealthiest elite. But they won, and a result, the poorest sections in the country would continue with no power at all until FDR’s New Deal would finally bring electricity to the rest of the country, or nearly 75% of the country that was just not profitable to company’s like PG&E.

Note that this history project has just begun, and will grow – check back!

CVP Stolen

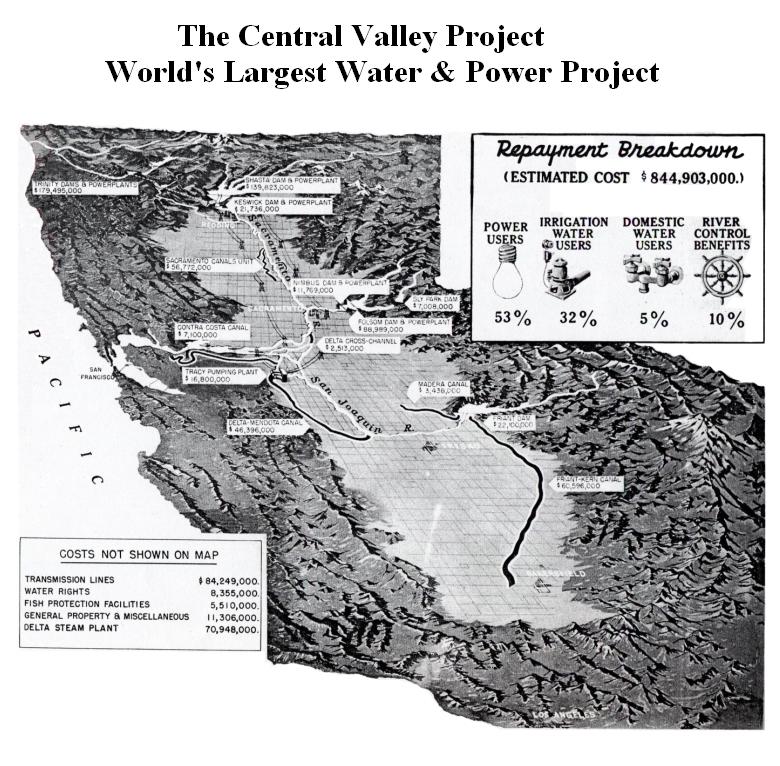

The ancient battle over who should control the power and water of the state had been blocked by allies of PG&E in the 1920’s when public power advocates put the issue on the ballot (see Chapter 54) a number of times. Finally, with the election of Franklin Roosevelt, the federal government went ahead with the massive Central Valley Project in 1933. The project would be the largest hydroelectric project in the world. The project would give tens of thousands of jobs to idle workers at the height of great depression. The proposal for such a major undertaking had been promoted for nearly 50 years as a way to stop the annual flooding and drought cycles so that intensive farming could take hold. From Shasta Dam in the North all the way to Bakersfield in the South, the project would change the state like no other, setting the stage for the statewide battles of the future.

The former SF Chronicle H de Roos would take his reporting of the Central Valley Project a step further and write a book called the Thirsty Land in 1948. In book’s chapter covering the “Power Politics” of the CVP, he would describe how PG&E would convince congress to block all funding for transmission lines to deliver the electricity to the waiting community coops that had been setup across California. The grid that would have delivered federal power to publicly owned cooperatives across northern California died in the hands of conservative representatives in Congress. PG&E would then build its private lines up to the massive Shasta and Friant dams, forcing the project into the company’s hands. Nearly all of the planned public power cooperatives in the state would die as a result.

This all but lost history of California’s past electric power wars will be updated in the future with far more details.